A story is told of how slaves across the whole of Africa were gruesomely ferried by their European slave masters across the Atlantic, as they headed to offer free labor in the latter’s cash crop plantations, and in their mushrooming industries in the 19th and 29th centuries.

A unique story, however, is told of how a group of Igbo people from modern day Nigeria, resisted slavery in the 19th century but instead, chose to drown themselves than bitterly taste the would- be untold suffering from their European masters.

This story popularly known as the Igbo Landing, has been documented by many authors across the globe but Larry Hobb’s version offers a more intriguing, captivating touch that makes it stand tall.

Larry Hobbs passionately narrates that the Igbo landing was an act of heritage acknowledgement, of self pride, of knowing and appreciating self worth that would later be monumentally written in history.

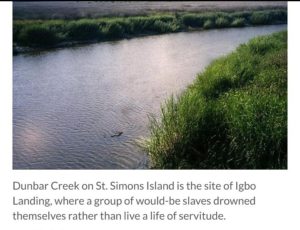

He writes that Dunbar Creek on St. Simons Island is the site of Igbo Landing, where a group of would-be slaves drowned themselves rather than live a life of servitude.

They were captured in Africa and hauled across the ocean against their will, eventually arriving in chains to the shores of St. Simons Island.

They may have been deemed mere chattel by the whites who bought them. You could call them prisoners of what is possibly the most brutish and shameful trade enterprise in human history. Bondsmen? Perhaps.

But these proud people of the west African Igbo tribe were not slaves. Oh, no — they were never slaves.

Rather than submit to an existence of bondage and forced labor at the hands of another, these products of proud warrior stock made a staggeringly poignant declaration of independence with their very lives.

It happened right here in the Golden Isles, way back in May of 1803. Some 13 members of the Igbo tribe walked as one in chains into St. Simons Island’s Dunbar Creek and drowned themselves rather than accept a life of slavery.

This striking testament to the harsh legacy of slavery is revered and preserved within the local African American community. It also is a much-cherished story among their descendants back in the Igbo homeland in present day southeastern Nigeria.

But there is little in the way of a public marker here on St. Simons Island to commemorate the Igbo’s resolve to live free or die. That seems a shame. Their sacrifice embodies the distinctly American traits of independence, self determination and, when forced, strong-arm rebellion in the name of freedom.

Like those 200 Texans at the Alamo in 1836, these Igbo gave their lives in a desperate last stand for that most treasured concept. Thus, they deserve an equally celebrated place in the hearts and minds of all Americans.

Chieftains of the Igbo tribe will be on St. Simons Island from their tribal homeland in Nigeria to pay homage to these distant kinsfolk, who died alone in a strange land so many generations past. These visiting dignitaries will consecrate the ground and pay tribute to their relatives with a ceremonial breaking of a native Kola nut.

“We value and recognize our dead,” explained Nigerian native Bobby Aniekwu, an attorney in Atlanta whose more formal title is Igbo Chieftain.

“Those who drowned may be still restless, so we have come to renew our ties with them and, through us, with their homeland. We must, because we believe they are always with us.”

The Igbo people claim ties to the tribes of Israel through the lineage of Gad, the seventh son of Jacob, Aniekwu explained. Their heritage is one of courage, fortitude and the inexstinguishable spark within the human spirit.

Indeed, the Igbo (sometimes referred to as Ebo) had gained a reputation throughout the slave-holding South for being virulently resistant to attempts at subjugation.

The story of Ebo (Igbo) Landing begins in Savannah, with the arrival directly from Africa of captives from that tribe. Mostly fact and part legend, versions of the journey from there vary somewhat. Approximately 75 of them were sold in 1803 at auction in Savannah, acquired for the plantations of John Couper on St. Simons Island and Thomas Spalding on Sapelo Island.

They were loaded upon the small sailing ship Morovia, bound first for Sapelo Island. By most accounts, however, the Igbo rebelled against the ship’s crewmen, who were either thrown or jumped overboard to their deaths. Aniekwu says Igbo history holds there were three crewman who were overpowered in what might be America’s first slave revolt.

“This story is very well known back home,” said Aniekwu, whose duties call him back there several times a year.

Regardless of its original destination, the Morovia came ashore in Dunbar Creek on St. Simons Island. It is there that a contingent of the captives went into the water in chains and drowned. Roswell King, a white overseer on Pierce Butler’s St. Simons Island plantation, stood witness to the macabre scene. He related that the Igbo “took to the swamp” and drowned rather than face a life in chains.

There is strong evidence to support this version of the events, eagerly supported by the island’s ghost tour guides.

As tradition holds, those chains made an eerie accompaniment to their dying chant as they followed a tribal leader into the river: “The Water Spirit brought us, the Water Spirit will take us home.”

In fact, generations of African American oral history speak of the defiant act as one of reverent salvation, not of death. Igbo spiritual traditions of the time informs us that they simply went home, returning by the waters from whence they came.

These Igbo were captured in the area of present day Nigeria’s Umballa River, upon which they were transported to the coast for the trans-Atlantic journey, Aniekwu explains. Their sad odyssey ended on Dunbar Creek, a river of sorts on Georgia’s Coast.

“They were thinking, We came by a river, and a river is going to take us home,” he said.

This rich story of The Igbo Landing helps us trace the roots of Pan Africanism – the spirit that was tirelessly defended in several ways by the sons of the soil.

Africans, Ugandans in particular, should continue to uphold this spirit for the generations to come.

Mama Africa has never been the dark continent it was dubbed to be by the white man. It never was! Let us continue to defy the odds. Let us continue to uphold the Pan Africanism spirit in all ways possible.